In other words, the -th element of the output sequence is the sum of the first elements of the input sequence.

Prefix sum is a very important primitive in many algorithms, especially in the context of parallel algorithms, where its computation scales almost perfectly with the number of processors. Unfortunately, it is much harder to speed up with SIMD parallelism on a single CPU core, but we will try it nonetheless — and derive an algorithm that is ~2.5x faster than the baseline scalar implementation.

#Baseline

For our baseline, we could just invoke std::partial_sum from the STL, but for clarity, we will implement it manually. We create an array of integers and then sequentially add the previous element to the current one:

void prefix(int *a, int n) {

for (int i = 1; i < n; i++)

a[i] += a[i - 1];

}

It seems like we need two reads, an add, and a write on each iteration, but of course, the compiler optimizes the extra read away and uses a register as the accumulator:

loop:

add edx, DWORD PTR [rax]

mov DWORD PTR [rax-4], edx

add rax, 4

cmp rax, rcx

jne loop

After unrolling the loop, just two instructions effectively remain: the fused read-add and the write-back of the result. Theoretically, these should work at 2 GFLOPS (1 element per CPU cycle, by the virtue of superscalar processing), but since the memory system has to constantly switch between reading and writing, the actual performance is between 1.2 and 1.6 GFLOPS, depending on the array size.

#Vectorization

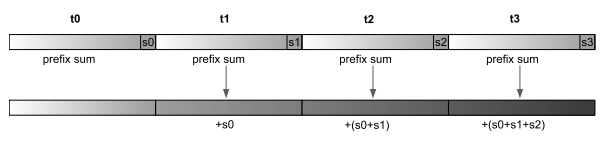

One way to implement a parallel prefix sum algorithm is to split the array into small blocks, independently calculate local prefix sums on them, and then do a second pass where we adjust the computed values in each block by adding the sum of all previous elements to them.

This allows processing each block in parallel — both during the computation of the local prefix sums and the accumulation phase — so you usually split the array into as many blocks as you have processors. But since we are only allowed to use one CPU core, and non-sequential memory access in SIMD doesn’t work well, we are not going to do that. Instead, we will use a fixed block size equal to the size of a SIMD lane and calculate prefix sums within a register.

Now, to compute these prefix sums locally, we are going to use another parallel prefix sum method that is generally inefficient (the total work is instead of linear) but is good enough for the case when the data is already in a SIMD register. The idea is to perform iterations where on -th iteration, we add to for all applicable :

for (int l = 0; l < logn; l++)

// (atomically and in parallel):

for (int i = (1 << l); i < n; i++)

a[i] += a[i - (1 << l)];

We can prove that this algorithm works by induction: if on -th iteration every element is equal to the sum of the segment of the original array, then after adding to it, it will be equal to the sum of . After iterations, the array will turn into its prefix sum.

To implement it in SIMD, we could use permutations to place -th element against -th, but they are too slow. Instead, we will use the sll (“shift lanes left”) instruction that does exactly that and also replaces the unmatched elements with zeros:

typedef __m128i v4i;

v4i prefix(v4i x) {

// x = 1, 2, 3, 4

x = _mm_add_epi32(x, _mm_slli_si128(x, 4));

// x = 1, 2, 3, 4

// + 0, 1, 2, 3

// = 1, 3, 5, 7

x = _mm_add_epi32(x, _mm_slli_si128(x, 8));

// x = 1, 3, 5, 7

// + 0, 0, 1, 3

// = 1, 3, 6, 10

return x;

}

Unfortunately, the 256-bit version of this instruction performs this byte shift independently within two 128-bit lanes, which is typical to AVX:

typedef __m256i v8i;

v8i prefix(v8i x) {

// x = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8

x = _mm256_add_epi32(x, _mm256_slli_si256(x, 4));

x = _mm256_add_epi32(x, _mm256_slli_si256(x, 8));

x = _mm256_add_epi32(x, _mm256_slli_si256(x, 16)); // <- this does nothing

// x = 1, 3, 6, 10, 5, 11, 18, 26

return x;

}

We still can use it to compute 4-element prefix sums twice as fast, but we’ll have to switch to 128-bit SSE when accumulating. Let’s write a handy function that computes a local prefix sum end-to-end:

void prefix(int *p) {

v8i x = _mm256_load_si256((v8i*) p);

x = _mm256_add_epi32(x, _mm256_slli_si256(x, 4));

x = _mm256_add_epi32(x, _mm256_slli_si256(x, 8));

_mm256_store_si256((v8i*) p, x);

}

Now, for the accumulate phase, we will create another handy function that similarly takes the pointer to a 4-element block and also the 4-element vector of the previous prefix sum. The job of this function is to add this prefix sum vector to the block and update it so that it can be passed on to the next block (by broadcasting the last element of the block before the addition):

v4i accumulate(int *p, v4i s) {

v4i d = (v4i) _mm_broadcast_ss((float*) &p[3]);

v4i x = _mm_load_si128((v4i*) p);

x = _mm_add_epi32(s, x);

_mm_store_si128((v4i*) p, x);

return _mm_add_epi32(s, d);

}

With prefix and accumulate implemented, the only thing left is to glue together our two-pass algorithm:

void prefix(int *a, int n) {

for (int i = 0; i < n; i += 8)

prefix(&a[i]);

v4i s = _mm_setzero_si128();

for (int i = 4; i < n; i += 4)

s = accumulate(&a[i], s);

}

The algorithm already performs slightly more than twice as fast as the scalar implementation but becomes slower for large arrays that fall out of the L3 cache — roughly at half the two-way RAM bandwidth as we are reading the entire array twice.

Another interesting data point: if we only execute the prefix phase, the performance would be ~8.1 GFLOPS. The accumulate phase is slightly slower at ~5.8 GFLOPS. Sanity check: the total performance should be .

#Blocking

So, we have a memory bandwidth problem for large arrays. We can avoid re-fetching the entire array from RAM if we split it into blocks that fit in the cache and process them separately. All we need to pass to the next block is the sum of the previous ones, so we can design a local_prefix function with an interface similar to accumulate:

const int B = 4096; // <- ideally should be slightly less or equal to the L1 cache

v4i local_prefix(int *a, v4i s) {

for (int i = 0; i < B; i += 8)

prefix(&a[i]);

for (int i = 0; i < B; i += 4)

s = accumulate(&a[i], s);

return s;

}

void prefix(int *a, int n) {

v4i s = _mm_setzero_si128();

for (int i = 0; i < n; i += B)

s = local_prefix(a + i, s);

}

(We have to make sure that is a multiple of , but we are going to ignore such implementation details for now.)

The blocked version performs considerably better, and not just for when the array is in the RAM:

The speedup in the RAM case compared to the non-blocked implementation is only ~1.5 and not 2. This is because the memory controller is sitting idle while we iterate over the cached block for the second time instead of fetching the next one — the hardware prefetcher isn’t advanced enough to detect this pattern.

#Continuous Loads

There are several ways to solve this under-utilization problem. The obvious one is to use software prefetching to explicitly request the next block while we are still processing the current one.

It is better to add prefetching to the accumulate phase because it is slower and less memory-intensive than prefix:

v4i accumulate(int *p, v4i s) {

__builtin_prefetch(p + B); // <-- prefetch the next block

// ...

return s;

}

The performance slightly decreases for in-cache arrays, but approaches closer to 2 GFLOPS for the in-RAM ones:

Another approach is to do interleaving of the two phases. Instead of separating and alternating between them in large blocks, we can execute the two phases concurrently, with the accumulate phase lagging behind by a fixed number of iterations — similar to the CPU pipeline:

const int B = 64;

// ^ small sizes cause pipeline stalls

// large sizes cause cache system inefficiencies

void prefix(int *a, int n) {

v4i s = _mm_setzero_si128();

for (int i = 0; i < B; i += 8)

prefix(&a[i]);

for (int i = B; i < n; i += 8) {

prefix(&a[i]);

s = accumulate(&a[i - B], s);

s = accumulate(&a[i - B + 4], s);

}

for (int i = n - B; i < n; i += 4)

s = accumulate(&a[i], s);

}

This has more benefits: the loop progresses at a constant speed, reducing the pressure on the memory system, and the scheduler sees the instructions of both subroutines, allowing it to be more efficient at assigning instruction to execution ports — sort of like hyper-threading, but in code.

For these reasons, the performance improves even on small arrays:

And finally, it doesn’t seem that we are bottlenecked by the memory read port or the decode width, so we can add prefetching for free, which improves the performance even more:

The total speedup we were able to achieve is between for small arrays and for large arrays.

The speedup may be higher for lower-precision data compared to the scalar code, as it is pretty much limited to executing one iteration per cycle regardless of the operand size, but it is still sort of “meh” when compared to some other SIMD-based algorithms. This is largely because there isn’t a full-register byte shift in AVX that would allow the accumulate stage to proceed twice as fast, let alone a dedicated prefix sum instruction.

#Other Relevant Work

You can read this paper from Columbia that focuses on the multi-core setting and AVX-512 (which sort of has a fast 512-bit register byte shift) and this StackOverflow question for a more general discussion.

Most of what I’ve described in this article was already known. To the best of my knowledge, my contribution here is the interleaving technique, which is responsible for a modest ~20% performance increase. There probably are ways to improve it further, but not by a lot.

There is also this professor at CMU, Guy Blelloch, who advocated for a dedicated prefix sum hardware back in the 90s when vector processors were still a thing. Prefix sums are very important for parallel applications, and the hardware is becoming increasingly more parallel, so maybe, in the future, the CPU manufacturers will revitalize this idea and make prefix sum calculations slightly easier.